Photography, Power & Others |Positions & Practice

The question of power balance is more at the forefront of my mind now than it would have been at the start of my practice. Starting out as a photojournalist the balance probably lay mostly with the audience in that the newspaper needed certain types of images and press photographers and photojournalists are generally trained to seek out those images, and in some circumstances manipulate scenarios for the purpose of illustrating a story.

Manipulation of scenes is fairly frowned upon in serious photojournalism and news reporting situations – though even in the Don McCullin’s Vietnam images there are instances where a scene was tampered with and laid out for photographic purposes over and above how the scene actually presented itself – but the photographer is always looking for the angle or composition that makes the photo and tells the story most effectively. Often the subject has the least power in these situations.

While I never worked in a war zone or even in a hard news environment – working mainly on regional newspapers and business publications – there were certainly instances where the story – ie what the audience ‘needed’ to see and be relayed – skewed both the photo and the power balance in a specific direction. I can think of one particular instance where my brief was to get a doorstep image of some local garage owners who were facing animal cruelty charges. The power balance didn’t feel in my favour as they chased me down the street but in actual fact the audience and myself as the photographer were certainly more in control of the final photo than the subjects were. In the circumstances where the news story is of importance and significance, and it is necessary to report in order to hold individuals accountable, I think the power imbalance can be justified. We get into trickier waters where the ‘news’ is less tangible or gossip or infringes on personal rights and privacy and the justification of ‘in the public interest’ is stretched.

In my current professional practice the balance is much more equal – my clients book me specifically to take certain types of photos but they book me based on my personal style of photography. Perhaps for branding and business clients, the audience is being manipulated to an extent in that the client is presenting their best self and selling themselves or their products and services so the images are being used for marketing purposes. However I think everyone involved is aware of this transactional nature of marketing and branding images, and my work is not high level big budget corporate advertising.

In my family client work I always seek consent before sharing any of the images in any forum and always reset consent if I use them for anything other than simple marketing of my services – for example where I have entered images into competitions or used them in publications. I strongly believe that if I’m commissioned to take images for a family they have the right to keep those images privately, and if I take images for one purpose, I should seek consent to use them for another.

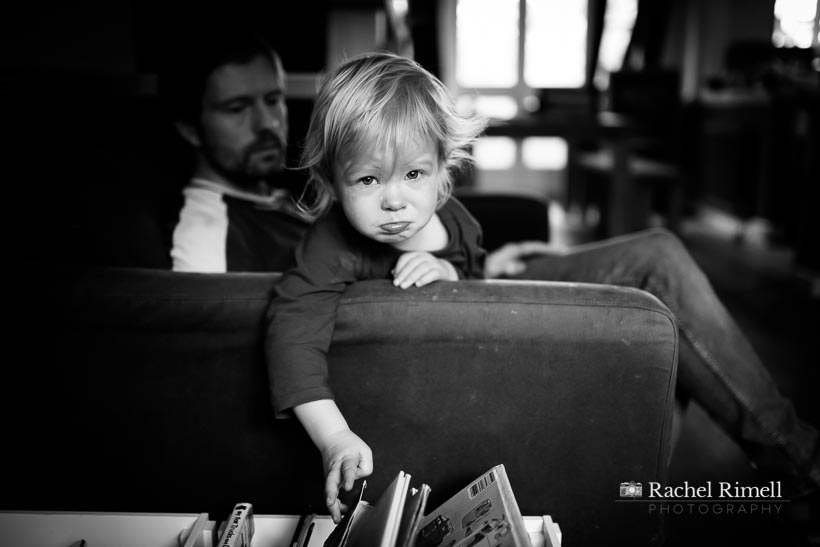

When photographing my own children, there is an issue around consent that I have considered but perhaps not in as much depth as I should have. It is now the social norm to share images of your children and family life. However in my position as a professional family photographer I have also shared images of my children in a professional capacity as a means of marketing my services and examples of my work and style. This does raise questions of consent. My children are currently young and it is possible they may as they get older not only refuse to be photographed but resent having had their images used in a public forum to market me as a business. They could equally resent having had them shared in a purely social capacity online, but the implications are subtly nuanced I think having used the images to sell a certain style of family photography – namely documentary family photography which is a bit of a ‘warts-and-all’ family album – and the moments it can capture and letting strangers in to see those family moments.

I have also at times felt, and reflecting back now feel, uncomfortable with images I have taken. This is particularly acute with regards to travel and street photography. I have always felt uncomfortable undertaking street photography and its not a genre I practice much. I had thought my unease was due to simply to feeling conspicuous taking photos on the street of strangers, but on reflection I think some of it has been a subconscious discomfort at the power imbalance whereby individuals on the street are being photographed without their consent and the images potentially used for purposes they have no control over. I recently went into London shortly after the first lockdown eased to photograph the streets while they were still relatively quiet and show a side of London rarely seen, in part to document this strange time. However as I was not being commissioned to make these images for a news purpose, it leaves me with a sense of being intrusive. I captured this image of a solitary mother breastfeeding her baby in The Scoop at More London. I think she is far enough away from the camera to be not easily identifiable, but I feel a little uncomfortable nonetheless that I captured on camera this private and quiet moment without her knowledge or consent.

I don’t think I have felt the same unease while doing travel photography – the role as tourist seems to legitimise street photography in a way that doesn’t apply on home turf. Except of course that it doesn’t and I am now increasingly conscious that travel street photography in many ways is ‘othering’ the people being photographed. They are ‘exotic’ to the eyes of the tourist. The scenes laid out are ‘culturally fascinating’. When in actual fact the people being photographed are simply everyday people living out their lives with foreigners considering them as artefacts and photographic souvenirs. I am particularly, in hindsight, uncomfortable with a particular image I took in Vietnam some 15 years ago of a woman walking down the street carrying the traditional yoke and baskets, who spotted me taking her photo and made gestures that she wasn’t happy to have her photo taken and/or wanted payment. The incident threw into sharp relief the fact that she was a person, not a tourist artefact for my entertainment. While I thought I was capturing a genuine street scene of real life, I was actually viewing it as a souvenir and I did not consider her right to give or refuse consent before I pressed the shutter. A similar situation reversed a few years back when when some Japanese tourists started to take photos of my young – quintessentially English-looking, blonde – children playing in their nappies in the fountains at London Bridge. Immediately I asked them to stop – mainly from online safety concerns where such images may be used – but the principle is the same and it highlights a double standard I am increasingly conscious of.

This is also something I’m aware of in the photography I consume, in particular questions around the ‘gaze’ and potentially ‘othering’ subjects and consent. Questions around consent and power balance and the responsibility of a photographer bring to mind The Waiting Game series Txema Salvans where he posed as a council worker in order to get clandestine photos of Spanish prostitutes where they worked on the streets. His undercover methods were controversially praised by Martin Parr but I find them extremely problematic, irresponsible and a classic example of where the male gaze and the story is deemed more important than the individual liberties of the woman subjects. Salvans accepted himself that the prostitutes did not consent to have their photos taken: he ignored these wishes and instead employed underhand and undercover tactics to get what he wanted, completely disregarding any concerns about their personal safety in being clearly identifiable in the resulting images.

References: